Here I shall argue that the doctrine of mereological constancy (MC), together with an innocuous premise, entails immaterialism, the thesis that each of us is numerically identical with an immaterial substance. What is MC?

(MC) It is impossible for a material object to gain or lose material parts.[1]

At first, MC seems palpably false. Surely if my body gains or loses an atom, it doesn’t cease to exist. Surely it continues to exist despite the fact that it gains or loses a part (this is, of course, compatible with its not being able to survive through significant change). But there is an excellent reason to think that MC is true, the denial of which requires one’s commitment to views that may seem to be more implausible.

I. The Paradox of Increase

Consider the paradox of increase.[2] Let A and B be any two material objects. When we attach B to A, have we made it such that B becomes a part of A? It seems not. It seems that we have created a new composite object, AB, and B does not become a part of A for A still exists as it was as part of the new composite substance. Similarly, we don’t make AB smaller when we remove from it B. AB is composed of both A and B, and removing B (perhaps by utterly destroying it) leaves us only with A. But it is palpably obvious that A is not identical to AB. Since destroying B leaves only A, and A ≠ AB, it follows that removing B causes AB to cease to exist. Since both of these arguments can be generalized, it follows that no material object can gain or lose material parts, that is, that MC is true.

We may also follow Olson and argue to MC as follows:

(1) A acquires B as a part [assumption for reductio].

(2) When A acquires B as a part, A comes to be composed of B and C.

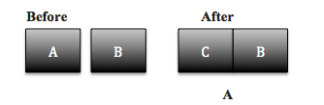

Since we are supposing that A gains a new part, B, we are not saying that there is a new object distinct from A. We are saying that A just is the object that now has B as a part, and C is the rest of A. The following illustration might help:

(3) C does not acquire B as a part [premise].

Of course, B doesn’t become a part of C, because both B and C exist, and both are distinct from A, which is the thing composed of both B and C.

(4) C exists before B is attached [premise].

It seems obvious that attaching B didn’t cause a new object, C, to suddenly pop into existence.

(5) C coincides materially with A before B is attached [premise].

C didn’t get any bigger or smaller when B was attached, and the things that composed A prior to B’s being attached now compose C, so it seems that C coincides with A prior to the attachment of B.

(6) No two things can coincide materially at the same time [premise].

(7) C = A [from 5 and 6].

(8) A does not acquire B as a part [from 3 and 7].[3]

Since our assumption in (1) entails a contradiction, namely, that A does and does not acquire B as a part, it follows that (1) is false.

II. The Argument to Immaterialism

One thing is clear. Olson doesn’t think the above argument, even if sound, entails immaterialism.[4] It turns out that he is wrong. We know that our bodies and brains are constantly changing, because they gain and lose material parts all the time. Let O1 be the organism/brain/body that I had at t1, and O2 the body I had at t2. Let P1 be me at t1 and P2 be me at t2. If I were a material substance, then (9) and (10) would be true:

(9) O1 = P1.

(10) O2 = P2.

It is obviously true that I persist through time. I am the same person that existed 10 years ago. So,

(11) P1 = P2.

It follows by transitivity that

(12) O1 = O2.

But MC entails that (12) is false and, indeed, necessarily false, because O1 and O2 are composed of different parts. Hence, it is false that I am a material substance. What this shows is that MC, together with the premise that I continue to exist through time and through changes in my body (I continue to exist when my body gains or loses an atom), entails immaterialism. Olson is therefore wrong: the paradox of increase is a good argument for immaterialism insofar as he is right when he argues that a rejection of any of the argument’s premises commits one to unsavory positions, such as sparse ontology (when one rejects 2), or constitution (when one rejects 6).

Leave a comment